This essay was published in Lawfare’s Research Paper Series. The official version that should be cited is linked here and a nicely formatted pdf is available here.

The essay is co-authored with Justin Curl, a third-year at Harvard Law School. Previously, he was a Schwarzman Scholar at Tsinghua University and earned a degree in Computer Science from Princeton, where we first collaborated. You can find more of his writing on AI and the law here.

Many AI leaders believe the technology will transform knowledge work. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman predicts AI systems that are “smarter than humans by 2030,”1 while Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei analogizes future AI models to a “country of geniuses in a data center.”2

Researchers identify legal services as especially vulnerable to disruption by AI.3 And since GPT-4 passed the bar exam,4 much of the profession seems to agree. Law schools have begun incorporating AI into their curricula5 and partnering with AI-focused legal-tech companies to prepare future lawyers for a changing profession.6 One prominent lawyer has argued AI can already replace law clerks and oral argument.7 Another predicts AI could “replace traditional lawyers by 2035.”8

This excitement about AI comes at a time when legal services are expensive. Millions of individuals are priced out of legal assistance,9 while corporate legal fees are increasing steadily, with hourly rates for partners at large law firms now exceeding $2,300.10 Unsurprisingly, many observers see the potential for AI to make legal services more accessible by delivering outcomes at lower costs.11

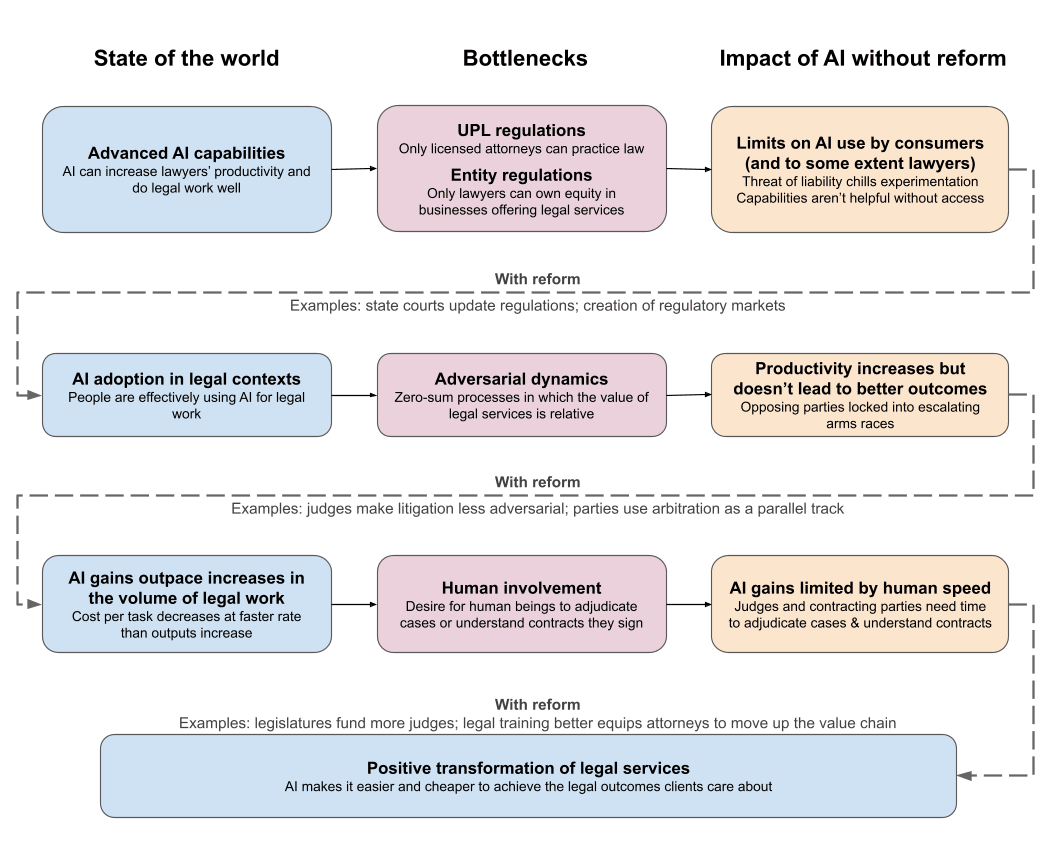

Our central claim is that advanced AI will not, by default, help consumers achieve their desired legal outcomes at lower costs. We examine the bottlenecks12 that stand between AI capability advances and the positive transformation of the practice of law that some envision. For AI to usher in a world of abundant legal services, the profession must address three bottlenecks: regulatory barriers, adversarial dynamics, and human involvement.

First, unauthorized practice of law (UPL) regulations may limit AI use by consumers (and to some extent lawyers). These laws prohibit nonlawyers from performing legal work.13 Individuals and organizations can face steep fines and criminal liability if courts conclude their systems cross into practicing law,14 forcing would-be providers to either limit their AI tools’ functionality in legal domains or risk enforcement actions. Entity-based regulations—which restrict who can own equity in businesses that provide legal services—restrict how legal services are offered, again limiting how AI is used by lawyers and consumers. Without reforms, if consumers cannot access AI capabilities or lawyers are not incentivized to use AI well, AI will not help people accomplish their legal goals, regardless of how advanced it becomes.

Second, even if AI is effectively and widely adopted, the American15 legal system’s adversarial structure can prevent advanced AI from lowering the cost of achieving clients’ outcomes.16 Because legal outcomes often depend on relative rather than absolute quality, when both parties become more productive, the competitive equilibrium simply shifts upward.17 In a world with advanced AI, achieving the same result—like settling favorably or prevailing at trial—would require a greater quantity and quality of legal work. So even as productivity increases and cost per legal task falls, parties are locked into an arms race of increasing amounts of legal work required to reach the same outcome.

As a historical analogy, digitization could have reduced discovery costs by making document review much easier.18 But litigators operating within litigation’s adversarial framework exploited the surge in digital documents to drive up costs for their opponents, leaving total litigation costs high.19

Though less explicitly adversarial, transactional work (like contract negotiation) can exhibit similar dynamics: Lawyers compete to control disclosures and outmaneuver opposing counsel when drafting and negotiating agreements.20 Of course, some legal outcomes (like effective estate planning) do not depend on adversarial processes, and this bottleneck would not apply to them.

The third and final bottleneck we discuss is human involvement in legal work. In a world where AI gains outpace increases in the volume of legal work, our desire for human beings to adjudicate cases and understand the contracts they sign is a final bottleneck. In litigation, if AI enables a flood of legal work, judges will likely respond by taking longer to resolve disputes (delaying outcomes) or delegate more to assistants (lowering adjudication quality).21 And with transactional work, even if AI is drafting entire contracts, human lawyers will still need time to understand what these provisions mean for an organization’s interests. The speed of human decision-makers (whether judges, lawyers, or clients) places an upper limit on how much AI can accelerate legal processes without sacrificing human involvement. See Figure 1 below for a visual description of the three bottlenecks and our argument.

This report applies the “AI as Normal Technology” framework to a specific domain: the legal industry.22 This framework is fundamentally about agency: Rather than treating AI’s trajectory as predetermined by capability advances, it directs attention to the social and organizational bottlenecks between what AI can do and the impact it has on the world. In our analysis of the practice of law, diffusion will likely be slow. Better models have not yet translated into more reliable legal products because adapting workflows to leverage AI and teaching users takes time.23

We argue that the end state of AI diffusion can look very different depending on the institutional response. Some pathways lead to genuine improvements in access and efficiency, while others simply make producing legal work (outputs) cheaper without making it easier to achieve the results clients want (outcomes). For AI to deliver better outcomes for consumers, the legal industry must enact reforms addressing the bottlenecks. Otherwise, we risk a future in which legal work becomes more abundant, but legal outcomes remain expensive and inaccessible.

We proceed in three sections. The first section explains why legal services are so expensive. The second section aims to convince readers that AI won’t automatically deliver legal outcomes at lower costs. And the third section offers recommendations for addressing these bottlenecks based on existing proposals for legal reform and illustrates how drastically AI’s impact could differ based on the legal profession’s response.

Table of Contents

Why Legal Services Are So Expensive

Three structural factors help explain why legal services are so expensive:24 Evaluating their quality is difficult, their value is often relative, and professional regulations limit competition from alternative business models.

First, unlike a meal at a restaurant, where it’s easy to assess quality, legal services are “credence goods,” which means their quality is difficult to evaluate even with hindsight.25 The final outcome in a case reflects the cumulative effect of many smaller decisions, so it can be very hard, even for other lawyers, to evaluate whether legal services were provided effectively.26 How clear was the law on that issue? Did the client reach the desired outcome because of or in spite of the lawyer’s skill? Which decisions actually contributed to that success? This evaluation difficulty forces consumers to rely on proxies for quality (e.g., the prestige of a lawyer’s law school or judicial clerkships) when choosing between legal service providers, making it hard for traditional market mechanisms to work.

Second, the value of legal services is relative.27 Because “the American litigation system is a thoroughgoing adversarial” one, what matters to the lawsuit’s outcome often isn’t how good your lawyers are in absolute terms, but whether they’re better than the other side’s.28 Other kinds of legal work, such as drafting contracts and agreements (often called transactional work), can also be adversarial as lawyers try to “outfox” each other in terms of what is disclosed in negotiations and the language of a contract itself.29

These dynamics have kick-started an arms race for legal talent, driving up costs at the top end of the market, which serves corporate clients and is often called “BigLaw.”30 In 2024, the median partner at large law firms charged $1,050 per hour, with some commanding over $2,300.31 That’s up 5.1 percent from 2023, which was itself up 5.4 percent from 2022.32 Fortune 200 companies reported that their average litigation costs in cases exceeding $250,000 in legal fees had nearly doubled over eight years, climbing from $66 million per company in 2000 to $115 million in 2008.33 In the patent field, a 2017 survey found that patent cases worth less than $1 million typically cost $1 million to litigate ($500,000 per side).34

Third, the profession’s regulatory framework, designed with consumer protection in mind, has created its own complications. Two types of regulations are often the focus of reform: unauthorized practice of law (UPL) and law firm ownership regulations.35

UPL laws make it illegal (in some jurisdictions a felony) for unlicensed attorneys to apply legal knowledge to specific circumstances.36 An unfortunate effect is to make it more expensive to offer basic legal assistance in contexts requiring little legal expertise.

Most states have regulations limiting who may share in legal fees. Gillian Hadfield argues that these rules promote a business model that creates inefficiency for small firms.37 These firms serve individuals and small businesses and are sometimes called the “PeopleLaw” sector.38 She cites a 2017 Clio study of forty thousand customers: In an average eight-hour workday, lawyers engaged in billable work for only 2.3 hours, billed 1.9 hours, and collected payment for just 1.6 hours.39 So although clients paid an average of $260 per hour, lawyers effectively received $25–40 per hour because the rest of their time was spent finding clients, managing administrative tasks, and collecting payments. These regulations require lawyers to serve clients through partnerships fully owned and financed by lawyers. They deter alternative models that involve large-scale businesses with centralized billing, customer service, marketing, and administrative functions, which could leverage economies of scale to deliver legal services at $30–50 per hour instead of $260.40

Importantly, none of the sources of market dysfunction are intrinsic to legal services. They reflect choices about procedure, pricing, and professional governance. While reform may be politically difficult or costly, the outlook is dim without it. And contrary to what some might hope, AI will not automatically make legal services cheaper, as we discuss next.

Why AI Won’t Help by Default

Regulatory Barriers

More legal assistance would be valuable in the debt collection context. From 1993 to 2013, the number of debt collection lawsuits grew from 1.7 million to about 4 million.41 In Michigan, these lawsuits made up 37 percent of all civil district court case filings by 2019.42 The trend is similar in Texas: “Debt claims more than doubled from 2014 to 2018, accounting for 30% of the state’s civil caseload by the end of that five-year period.”43 More than 70 percent of debt collection defendants lose by default for failing to respond, even though many cases are “meritless suits” and responding is not complicated.44

New York has created a form for responding to debt collection lawsuits by checking some boxes.45 This form, however, includes questions difficult for nonlawyers to understand, such as whether someone would like to invoke the doctrine of “laches.” Recognizing this difficulty, the nonprofit Upsolve began training volunteers to offer assistance. Concerned that this might violate New York’s UPL rules, Upsolve sought an injunction declaring this basic assistance was protected by the First Amendment. A federal judge agreed.46 But New York appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, which invalidated the injunction, concluding that the lower court applied the wrong First Amendment test (so Upsolve was no longer protected).47

It’s easy to see how an AI system could help here. A nonprofit could provide access to a tool customized for debt collection suits. Or individuals could directly ask general-purpose tools like ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini for relevant information. Despite this potential, organizations risk violating UPL laws whenever their AI tools complete “tasks that require legal judgment or expertise.”48 The New York Bar Association, concerned that the shortcomings of current AI models would harm consumers, has warned that “AI-powered chat bots now hover on the line of unauthorized practice of law.”49 While some legal researchers disagree because AI is not a “person” capable of exercising legal judgment50 or because AI systems simply “provide information to users, similar to paper guides about court procedure,”51 all authors cited in this paragraph agree that the status of AI tools under UPL laws is currently unclear.

LegalZoom’s history of lawsuits illustrates how UPL regulations can deter innovation in the delivery of legal services.52 LegalZoom automates rote tasks like preparing documents for trademark filings and has been plagued by UPL lawsuits for years.53 In 2011, private individuals who had purchased the company’s services sued in Missouri, alleging LegalZoom was engaged in UPL because it claimed to “take[] over once a consumer answer[ed] a few simple online questions.”54 After the court denied its motion to dismiss the case, LegalZoom agreed to compensate plaintiffs and modify its business model. In 2015, the North Carolina State Bar won a consent judgment requiring LegalZoom to conform to certain conditions.55 Trademark lawyers in California advanced similar theories in a 2017 suit against LegalZoom’s trademark-filing product.56 And in 2024, a New Jersey plaintiff brought a class action alleging UPL violations.57

While AI’s legality remains in doubt, the threat of UPL liability can inhibit its adoption. Without reform, developers risk fines and criminal liability if their AI systems provide legal advice. Organizations may simply be unwilling to provide access to users, especially those who cannot afford to compensate a developer for the risk of UPL liability. Separately, entity regulations that restrict financing for AI legal startups can deter the kinds of operational experimentation helpful for delivering legal services at lower costs. Overall, if regulatory barriers prevent consumers from effectively accessing AI capabilities, it will not translate into better legal outcomes for clients at lower costs.

That said, AI could reduce the costs of legal services for reasons unrelated to its ability to perform legal tasks. As the 2017 Clio survey mentioned above found, nonlegal work consumes a large percentage of lawyers’ time at the low end of the market. If advanced AI helps find and communicate with clients, manage administrative tasks, and handle payments, it could free up these lawyers to spend more time on legal work.

Adversarial Dynamics

Even in a world in which AI increases lawyers’ productivity and completes legal tasks, it might not lower the costs of legal services. To see why, it is crucial to distinguish inputs and outputs from outcomes. Inputs are what goes into legal work: employee talent, billable hours, and technological tools. Outputs are what legal work produces: contracts drafted, motions filed, and briefs written. Outcomes are what clients actually care about: disputes resolved, deals closed, and rights protected.

Consumers purchase legal services to achieve specific outcomes. Inputs and outputs can indirectly lead to those outcomes because more hours worked and more legal tasks help clients get the outcomes they want. But in a zero-sum context where the value of legal services is relative, if both sides increase their outputs, the advantages to either side of doing so can be limited.

Instead, AI might simply raise the inputs and outputs required to reach the same outcome, with productivity gains absorbed by greater production. The billable hours model, in which lawyers are paid and promoted based on inputs, only reinforces these dynamics: More hours worked drafting motions and reviewing documents translates into greater revenue for legal firms without necessarily improving outcomes.

Litigation

One response is that these arms races actually create value by increasing the quantity and quality of legal work. However, clients sometimes achieve their desired outcomes (like settling a case or dismissing a lawsuit) by imposing greater costs on the other side instead of improving the quality of their legal arguments or evidence. It is a “core premise of litigation economics”58 that “all things being equal, the party facing higher costs will settle on terms more favorable to the party facing lower costs.”59 And even where quality does improve, it’s uncertain that the benefits of higher quality legal work (like helping courts reach the “right” answer more often) outweigh the costs of more legal work (like overwhelming judges with cases).

Earlier technological shifts cast doubt on whether America’s “adversarial legalism” can translate productivity gains into more affordable legal services.60

Discovery is a cornerstone of American litigation that often determines whether cases settle or go to trial. In discovery, parties share information “to identify material facts that prove or disprove a claim.”61 It operates through an adversarial exchange: One party sends a discovery request; the other searches its records and decides which documents are responsive and which are protected by privilege.

Discovery was conceived of as a cooperative process during which lawyers could share information to facilitate settlement and avoid trial.62 Yet two characteristics of discovery make it vulnerable to abuse. First, the party holding the documents (the reviewing party) knows what’s in them but seeks to share as little helpful information with the requesting party as possible to minimize legal risk. Second, the reviewing party, because they bear the responsibility and costs for producing documents, must essentially act as their adversary’s agent.

Each side can leverage these features to impose costs on the other. A requesting party, through excessive requests, can compel their adversary to review more documents for confidentiality and relevance. And a reviewing party, through excessive production, can bury relevant information in mountains of extraneous material, forcing the opposing side to spend more time on review. This can create an arms race of overrequesting and oversharing, as each side drives up costs for the other to pressure them to settle on more favorable terms. The billable hours model again reinforces this behavior, with more review generating more billable hours.

These adversarial incentives can be powerful. Judge Frank Easterbrook opened a well-known article, “Discovery as Abuse,” by analogizing the process to “nuclear war.”63 Charles Yablon described how one side made life difficult for opposing counsel: It printed documents on dark red, foul-smelling paper so that their contents would be nearly illegible and the attorneys would get nauseous reviewing them.64 As Arthur Miller aptly observed, discovery’s key defect was believing “that adversarial tigers would behave like accommodating pussycats throughout the discovery period, saving their combative energies for trial.”

Digitization might have pushed discovery costs in either direction.65 Better search capabilities meant attorneys could review documents more efficiently, driving down costs while increasing the relevance of information shared. Yet the explosion of digital information increased what parties might need to search through during discovery, creating more opportunities for discovery abuse.

The empirical evidence on discovery is limited, so making causal claims about digitization’s impact is difficult.66 The available evidence, however, suggests it remains expensive. Discovery accounts for roughly “one-third to one-half of all litigation costs” when used.67 Fortune 200 companies reported that in cases with over $250,000 in legal fees, which are typically the kinds of complex litigation that require discovery, average litigation costs nearly doubled from $66 million per company in 2000 to $115 million in 2008.68 These figures align with evidence of over-requesting and oversharing: One trade association for civil defense lawyers estimated that for every page eventually shown at trial, meaning it’s relevant and reliable enough to be used as evidence, over one thousand pages were produced in discovery.69

The main lesson of digitization, then, is that adversarial processes do not translate predicted productivity gains into lower-cost legal outcomes by default. David Engstrom and Jonah Gelbach hope that Technology Assisted Review (TAR) software, which uses predictive AI to classify documents for privilege and confidentiality based on an initial training set of labeled documents, can eventually solve discovery’s inefficiencies.70 Yet they acknowledge this is far from guaranteed given litigation’s adversarial structure. And because federal rules require discovery requests to be “proportional” to a case’s needs, judges might respond to declining unit costs of discovery (the cost of producing each document) by authorizing more expansive discovery plans, leaving total costs high. Though discovery is important, it is not uniquely susceptible to adversarial dynamics. An arms race of legal work in any stage of litigation (e.g., pretrial motions, expert battles, appeals) can erode efficiency gains and make achieving clients’ objectives expensive.

Transactional Work

Similar adversarial patterns appear in transactional work like negotiating and drafting contracts. Hadfield illustrates how their value can be relative using an example of a merger agreement negotiation.71 In such negotiations, skillful lawyers can improve their client’s position by limiting disclosures, “skating the line between legitimate silence and misrepresentation.”72 Opposing counsel will try to stay one step ahead by deciding what to ask, which representations to seek, and how to interpret disclosure laws to reduce the likelihood that material information is withheld.73 Lawyers will also try to “outfox” each other in the language of the contract itself.74

In the event of future litigation, the clients whose lawyers misunderstood a term’s significance pay the price. Since one can always do more legal research or add more contract provisions, there is no natural limit on the capacity for additional legal work to absorb efficiency gains. And because contracts concern future obligations, added uncertainty makes it harder for clients to effectively compare the quality and price of legal services.

Contracts have grown longer and more complex over time. From 1996 to 2016, M&A agreements expanded from 35 to 88 single-spaced pages, their linguistic complexity increasing from post-graduate “grade 20” to postdoctoral “grade 30.”75 An analysis of privacy policies over a similar period found a similar trend.76 John Coates argues that the increases in length and complexity reflect necessary and valuable responses to emerging legal risks.77 While longer, more complex contracts may represent better agreements, they might be necessary only in a legal system as adversarial as America’s, where litigation risks are high. Some scholars argue German contracts deliver similarly satisfactory legal outcomes with fewer words.78

That said, though transactional work has the adversarial elements described above, the overall structure is less adversarial than litigation. Because contract negotiations take place before a dispute occurs, there are more opportunities for transactional attorneys to add value beyond securing more of a fixed set of resources for their clients in a zero-sum negotiation.79

Human Oversight

A third bottleneck is our desire for human involvement. This is most relevant when AI gains outpace increases in production, which could happen for a few reasons. Perhaps there is an upper limit on arms races for certain kinds of legal work. After all, some legal doctrines are only so complicated, and courts often impose strict page limits on filings. Or maybe AI is so advanced that the costs of all legal tasks fall basically to zero and increased production does not absorb productivity gains. In this scenario, the new bottleneck for litigation would be the time required for judges to resolve cases, and for transactions, it would be the time parties need to understand a contract’s terms.

Starting with litigation, by reducing the cost of filing an initial lawsuit, AI will likely result in more disputes ending up in court. Within each dispute, AI can then create the kind of arms race of outputs described above. As a very rough but conservative estimate, Yonathan Arbel predicts a two- to fivefold increase in the volume of litigation.80

Arbel outlines several ways that judges might respond to a flood of litigation.81 They could limit the flow of litigation by altering procedural and substantive doctrines to make it harder for litigants to get into court (creating a bottleneck related to regulatory barriers). Or they could try to limit the use of AI in the courtroom, perhaps by requiring lawyers to disclose AI use or banning AI entirely and sanctioning any violators. Both responses would counteract a flood of litigation work but come at the steep cost of sacrificing access to justice for poorer litigants.

The debt collection context also provides an uninspiring picture of how courts have managed a flood of cases.82 As technology has enabled collectors to buy outstanding debt and cheaply file lawsuits for enforcement, the explosion of debt collection lawsuits has overwhelmed state courts.

Some have resorted to delegating cases to court assistants. Others operate “judgeless courtrooms” with lax evidentiary standards that can lower the quality of adjudication and can undermine the rationale for the judicial process itself.83 If judges do not delegate, adjudicating cases will take longer as both the number of cases and the work each requires expands. Yet as the common legal maxim says: “Justice delayed is justice denied.” Although more people might gain access to court, if judges require years to adjudicate cases, plaintiffs will face a choice between protracted litigation with no guarantee of success and settling cases on increasingly unfavorable terms as resolution times lengthen.

Another option is incorporating AI into the judicial process to ease the strain on overwhelmed courts.84 One early report suggests that AI is helping Brazil’s courts resolve cases more quickly.85 Yet if AI advances continuously reduce filing costs and drive up legal outputs, it will grow increasingly difficult for judges to keep pace. Perhaps AI will make judges more efficient. But there is a limit to how much AI can accelerate the process without meaningfully sacrificing human involvement.

Some seem open to replacing human judges entirely with AI.86 We find the legal (Article III, which establishes the federal courts, likely requires human judges),87 technical (hallucination and private influence problems),8888 and moral objections persuasive.89 Even avowedly pro-AI lawyer Adam Unikowsky acknowledges he is “not quite ready to be ruled by robots.”90 This is not to say that there is no role for AI in judging. But judges should adopt AI through careful, deliberate choices instead of in ways compelled by the need to keep up with an arms race of AI-powered legal work.

The argument for contracts is similar. If advanced AI reduces the cost of drafting contracts (perhaps it can instantly draft 50 perfect provisions), a contracting party, even with the help of AI, will still need time to understand what those provisions do and how they impact the party’s future interests.

This bottleneck would not apply if people were to forgo oversight. Arguably, human involvement matters less for contracts because many Americans already agree to contracts (like privacy policies) without reading them.91 But we think this reflects the belief that they have insufficient bargaining power to negotiate new terms, or that it’s not worthwhile to do so, rather than a general endorsement of signing contracts they don’t understand.

All this to say, we believe some measure of human involvement in the legal system is valuable and necessary, though this is a normative position and not an empirical claim.

Institutional Reforms

Many problems facing the legal industry are not new. For decades, legal academics and practitioners have suggested reforms targeting the bottlenecks described above. Some address AI specifically, others are more general, and a few are already being tested in various states and jurisdictions. In this section, we organize proposals into three categories, each corresponding to a bottleneck above: the regulation of legal services, the adjudication process, and the evolving role of human beings in legal work. While we aren’t tied to any particular recommendation, we discuss a range of reforms to illustrate that the future of the practice of law could look very different depending on how institutions respond (or decline to respond) to AI.

Reforming Professional Regulation

A chorus of voices have suggested reforms to the legal profession’s self-regulations.92 Their recommendations range from clarifying existing UPL laws to modifying law firm ownership rules to overhauling how the profession itself is regulated.93 Some are already being tested.

Clarifying Unauthorized Practice of Law Rules

Current UPL laws define practice of law imprecisely and may prohibit companies from offering AI-powered legal assistance to consumers. Some jurisdictions are expanding who may provide legal services, and academics have proposed updates with AI in mind.

Creating a new tier of legal service providers is one of the “fastest growing UPL reform program types” nationally, with seven states adopting this approach and another ten considering it.94 David Autor argues these reforms would benefit all professions by allowing people, in combination with AI, to work at levels of expertise previously unavailable to them. He analogizes to the creation of the nurse practitioner role.95 In the early 1960s, nurses and doctors developed training programs and successfully lobbied the American Medical Association to create a new class of medical professionals who could perform tasks previously reserved for doctors.96 Other researchers offer a more concrete framework for how state courts might design this tier of legal service provider.97

Joseph Avery and co-authors propose more ambitious reforms: allowing nonlawyers, including AI systems, to offer many legal services.98 Bar associations would retain authority over who may use the designation of “lawyer,” but nonlawyers could provide any legal service other than representing clients in court.99 This would allow companies and nonprofits to offer AI-enabled services to consumers without claiming they are licensed attorneys and without the threat of UPL litigation. The prospect of being sued for negligent work would still serve as a quality backstop for lawyers and nonlawyers alike.

Sean Steward, by contrast, takes no position on where to draw the line between acceptable and unacceptable uses of AI, instead emphasizing the need for clear, nationwide rules to reduce burdens on providers.100 Drew Simshaw likewise advocates a nationwide approach to eliminate the patchwork of vague, conflicting rules.101

To be clear, the problem with existing UPL rules is not that they are regulations and therefore stifle innovation. It is that their uncertainty and variation discourage competition from new entrants, including the kind that produces better legal services.

Alternative Business Structures

Legal scholars have long argued for updating “entity regulations” that prevent nonlawyers from sharing fees from or investing in law firms.102 Utah and Arizona recently created regulatory sandboxes to do exactly that.103 Utah’s sandbox allows entities to seek waivers from ownership restrictions and UPL rules, while Arizona eliminated restrictions on law firm ownership and fee-sharing. These sandboxes permit companies and nonprofits to operate under modified professional rules while regulators assess their impact on service quality, cost, and access to justice.104

These sandboxes treat regulatory experimentation as necessary for balancing protection and innovation for consumers. Overly stringent restrictions can backfire by protecting inefficient incumbents or forcing new entrants outside the law. Uber and Airbnb succeeded, in part, by accepting regulatory fines, scaling quickly, and becoming so ubiquitous that lawmakers had little choice but to legalize their conduct. Yet overly lax restrictions can undermine the regulations’ purpose: protecting consumers from poor quality services. Sandboxes allow policymakers to experiment and evaluate different regulatory approaches.

Early evidence on the impact of these reforms has been largely positive, though concerns have emerged regarding private equity ownership and mass tort litigation financing. Despite scant evidence of consumer harm—Utah’s Office of Legal Services Innovation received only twenty total complaints —lawyers and commerce groups petitioned the Arizona and Utah supreme courts to limit these sandboxes. The Arizona Supreme Court stayed the course, and authorized entities grew from nineteen to 136 between 2022 and 2025.105 The Utah Supreme Court has since raised eligibility requirements, and authorized entities shrank from thirty-nine to eleven over the same period.106

Regulatory Markets

Gillian Hadfield proposes a “superregulator” model that would create a market for the regulation of legal services.107 Rather than regulating providers directly, the government would license regulators that would each offer competing regulatory schemes. The government’s role shifts to “regulating the regulators” by setting outcome targets, such as acceptable levels of legal access or dispute resolution quality, and then licensing regulators that achieve them.

Hadfield argues this generates powerful incentives for innovation.108 A private regulator that develops simpler, more cost-effective compliance methods while meeting government standards will attract more customers. The model can also simplify enforcement: Governments can monitor ten licensed regulators more easily than thousands of individual providers.

We would add that regulatory markets may be able to assess AI’s utility for legal services more reliably than benchmarking.109 Two of us have emphasized that task-oriented benchmarks lack construct validity because they “overemphasize precisely the thing that language models are good at” while failing to test the contextual understanding and sustained reasoning that characterizes consequential legal work.110 Benchmarks can also miss hidden costs that emerge only over time, such as deskilling of professionals.111 Relatedly, by targeting entry-level tasks, AI can disrupt the pipeline through which junior lawyers develop expertise.112

Hadfield defends the proposal’s practicality by drawing parallels to existing models. Governments already use outcomes-based regulations in environmental law, and private standard-setting bodies design many regulations currently in use. The United Kingdom provides one example. Under the Legal Services Act 2007, Parliament created the Legal Services Board (LSB), an independent agency that approves private bodies applying to regulate legal services.113 The system is not yet fully competitive because regulators came from preexisting trade associations for barristers and solicitors, which together regulate 90 percent of legal professionals in England and Wales.114 But competition is emerging for “alternative business structures,” which can choose between licensing from the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) or the Bar Standards Board (BSB).115

This U.K. model has, however, encountered difficulties. In October 2024, the LSB criticized the SRA for failing to “act adequately, effectively, and efficiently” before the law firm Axiom Ince collapsed in October 2023.116 The LSB issued a report in March 2025 expressing “serious concerns” about the SRA’s effectiveness and then recently proposed sanctions.117 This highlights how superregulators can struggle to enforce quality standards for the regulators it oversees. Some scholars have separately criticized regulatory markets in other contexts for creating a race to the bottom. For example, Daniel Schwarcz cautions that a market for insurance regulation could “trigger a ‘race to the bottom’ as regulators compete with each other to offer less and less intrusive regulatory schemes.”118

Reforming Adjudication

Another set of reforms targets case adjudication. Some aim to make the trials less adversarial, while others advocate for private adjudication like arbitration.

Judicial Case Management

Judges have some discretion over the litigation process and can exercise it to reduce adversarial dynamics. Several judges have recommended leveraging existing rules of evidence and civil procedure to manage cases more actively, taking inspiration from other jurisdictions (often called inquisitorial systems).119 Such targeted borrowing can help reduce competitive escalation.

One example is allowing courts to appoint their own expert witnesses. Under Federal Rule of Evidence 706, judges can appoint neutral experts that work for the court but are paid for by both parties.120 One state trial judge argues this can solve the “battle of experts” problem where competing specialists “abandon objectivity and become advocates for the side that hired them.”121 When technical issues are central to a case, court-appointed experts can provide neutral assessments that frame issues more productively, avoiding an arms race of dueling expert reports.122

Another tool is the use of “special masters” under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 53.123 These are neutral third parties appointed to help manage complex aspects of cases. A federal judge and senior litigator explain that special masters can “assist and, when necessary, direct the parties” to complete discovery efficiently.124 They note that the 2003 amendments expanded the scope of special masters’ use to include pretrial matters “that cannot be effectively and timely addressed by an available district judge.”125 Rather than having parties fight over AI-assisted document review through successive motions, a special master could serve as an intermediary and prevent the technology from enabling larger discovery battles.

Judges currently have the discretion to intervene under these rules, but Congress could also pass legislation that makes them mandatory.

Arbitration

While disputes are normally resolved through litigation, some contracts specify private arbitration.126 Contract drafters might prefer this process for several reasons: It can resolve disputes at lower costs,127 reduce class-action exposure,128 and prove “more flexible and less adversarial … than its judicial counterpart.”129 Arbitration has become a popular alternative to traditional litigation.130

Two legal scholars argue that because arbitration grants parties autonomy over the process, it’s the “ideal entry point for broader AI adoption in the legal field.”131 They defend AI arbitration as consistent with the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) and desirable for enhancing “efficiency, fairness, and flexibility of dispute resolution.”132 Another scholar takes the opposite stance, arguing that the FAA does not permit AI arbitration because robot adjudicators are inconsistent with the statute’s use of human pronouns like “he or they.”133 And still another views it as undesirable because it would “significantly diminish the long-standing reputation” of arbitration.134

Some observers critique arbitration as unfair because companies often force it on consumers and employees through “take-it-or-leave-it” contracts of adhesion.135 These fairness concerns are important, and others have written about the level of consent needed for arbitration to be truly fair.136 But assuming the decision to enter arbitration reflects the free choice of both parties, offering AI arbitration as a parallel track for resolving cases can have several advantages.

First, it can promote choice by allowing litigants to decide between traditional judicial review and AI-assisted adjudication.137 A consumer defending against an automated debt collection suit might prefer quick AI resolution over years of waiting, while a defendant facing serious consequences might insist on traditional review by human judges.

Second, should an arms race of legal outputs risk overwhelming the courts, the availability of a technology-mediated alternative can alleviate pressure on the courts, preserving human review for the contexts where those navigating the judicial system feel they need it most.138

Third, it creates a natural experiment that facilitates comparison between human and AI adjudicators on dimensions like speed, cost, and participant satisfaction.139 This generates evidence about AI’s actual performance, reducing reliance on speculation or vendor claims, and it pressures traditional institutions to improve or risk being outcompeted.140

The Evolving Role of Lawyers

A final set of reforms discusses the evolving role of lawyers in both litigation and transactional contexts. With litigation, legislatures could expand the judiciary to alleviate the bottleneck created by the time human judges take to resolve cases. With transactions, there isn’t a clear action item for companies, but we expect to see a shift in what in-house counsel do. As the bottleneck becomes the time it takes human lawyers to understand complex contracts, in-house lawyers will likely spend more time understanding a company’s needs and making strategic judgments and less on legal tasks.

Expanding the Judiciary

The most straightforward response to an overburdened judiciary is to increase its capacity by hiring more judges. Legal scholars have advocated for this solution for decades.

For example, writing in 1979, Maria Marcus argued that “[s]ince the factors that channel disputes into a judicial forum continue unabated, the appointment of more judges is an obvious response.”141 Bert Huang again recommended in 2011 that “new demands put on the courts should be met quickly and flexibly with new judicial resources.142 More recently, Peter Menell and Ryan Vacca endorsed an observation from decades earlier that “the increase in the order of magnitude of the demands our society imposes on the federal judicial system” should encourage Congress to act.143

Menell and Vacca acknowledge that “[i]ncreasing the number of federal judgeships has been fraught with political complications.” Their solution is a bipartisan “2030 Commission” to depoliticize the process.144 Arbel similarly views adding judges as “the most direct way of solving the problem” of an AI-driven increase in litigation work, yet stops short of recommending it because it “appears quite tenuous in our current political reality.”145 He notes that redirecting all civil legal aid funding (approximately $2.7 billion) toward the $9.4 billion federal court system would yield at most a 30 percent increase in judicial capacity, falling short of the doubling likely needed to handle the increased caseload.146

But civil legal aid is not the only potential funding source. Some states have proposed taxing legal services generally,147 while federal legislation introduced by Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.) would tax third-party litigation financiers who fund plaintiffs’ legal fees in exchange for a percentage of eventual winnings.148 Although these bills aim to increase overall tax revenues, similar measures could earmark funds specifically for the judiciary. Deborah Rhode has proposed another approach: mandatory pro bono service requirements for all attorneys, with the option to “buy out” their obligation.149 Though initially conceived as a way to provide access to justice, these payments could also support judicial expansion.

So while we agree that expanding the judiciary faces real political obstacles, we don’t think it’s as unrealistic as Arbel fears, especially considering the magnitude of AI’s potential disruption.

In-House Counsel as Strategic Advisors

Our analysis suggests that among in-house lawyers, value will likely shift from completing tasks to predicting how contracts and agreements impact the overall business. Lawyers will need to deeply understand their organizations and exercise business judgment.

Industry reports agree.150 In a 2023 survey of nearly three hundred chief legal officers, 87 percent said their role is shifting from legal risk mitigator to strategic business partner.151 Thomson Reuters’s 2024 “Future of Professionals Report” found that 42 percent of legal professionals expect to spend more time on judgment-based legal work in the next five years, as AI handles more routine tasks.152 As one attorney respondent put it: “The role of a good lawyer is as a ‘trusted advisor,’ not as a producer of documents … breadth of experience is where a lawyer’s true value lies and that will remain valuable.”153

To understand the shifting role of legal professionals, it is helpful to consider the hierarchy of legal work and roles. At the bottom is basic “low-skilled” legal work like drafting standard letters or simple contracts, repetitive tasks requiring minimal legal expertise.154 Above that is medium-skill, noncommoditized legal work that involves producing documents, such as analyzing contracts and drafting motions.155 Higher still is “judgment-based legal work”: overseeing complex trials and addressing legal risks.156 At the top is strategic advising, where lawyers deeply understand an organization’s priorities and shape its decisions.157 This highest level might not involve what we traditionally consider legal work at all.

As AI pushes the role of human expertise up this hierarchy, the legal profession should rethink how it trains lawyers. While AI automates the tasks at the bottom of the hierarchy, demand will likely grow for lawyers at the top who can translate legal information into strategic advice. One bar association warned that the “greater concern is that generative AI will displace younger attorneys,” who will “have fewer opportunities to gain valuable experience by spending hours on important tasks.”158 As the skills required to succeed change, so too should the training process.

Conclusion

Many problems facing the legal industry do not require revolutionary insights to solve. Scholars and practitioners have long emphasized the need for regulatory reform, changes to the litigation process, and the disconnect between legal work and client outcomes. AI, rather than solving these problems, appears to be revealing and magnifying them. Without addressing these underlying issues, AI alone is unlikely to improve the outcomes clients care about.

But AI may also present new opportunities for reform. Sociologists have argued that fields facing crises are more receptive to efforts to reshape institutions in those areas.159 Such crises, jolts, shocks, and disruptive events—taking the form of social upheaval, technological disruption, or other changes—can reveal problems and contradictions that require solutions. The widespread predictions that AI will transform the practice of law may constitute such a crisis, creating pressure for legal institutions to respond. The key question is whether they can use this opportunity to enact the reforms the industry has needed for decades and produce better outcomes for clients.

Acknowledgments: We are grateful to Samar Ahmad, James Bedford, Jasper Boers, Lev Cohen, Joe Goode, Mihir Kshirsagar, Martha Minow, Ben Press, and Jonathan Zittrain for helpful feedback on this report.

Jan Philipp Burgard, “Sam Altman Predicts AI Will Surpass Human Intelligence by 2030,” Business Insider (Sept. 26, 2025).

Dario Amodei, “Machines of Loving Grace: How AI Could Transform the World for the Better” (October 2024), https://perma.cc/8CPH-TJ63.

See, e.g., Edward W. Felten, Manav Raj, & Robert Seamans, “Occupational Heterogeneity in Exposure to Generative AI” (April 10, 2023) (unpublished manuscript), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4414065.

See Daniel Martin Katz, Michael James Bommarito, Shang Gao, & Pablo Arredondo, “GPT-4 Passes the Bar Exam,” 382 Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (2024), https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2023.0254.

Karen Sloan & Sara Merken, “AI Training Becomes Mandatory at More US Law Schools,” Reuters (Sept. 22, 2025); University of San Francisco, “The University of San Francisco School of Law Embeds GenAI Into Core Curriculum” (April 16, 2025), https://perma.cc/2RSV-ZZGA.

Harvey, “Harvey Launches Academic Program With Law Schools at Stanford, NYU, Michigan, UCLA, The University of Texas, and Notre Dame” (Aug. 28, 2025), https://perma.cc/77Q3-C5P6.

Adam Unikowsky, “Should AI Replace Law Clerks?,” Adam’s Legal Newsletter (Jan. 20, 2023), https://perma.cc/A7WN-4T9A; Adam Unikowsky, “Automating Oral Argument,” Adam’s Legal Newsletter (July 7, 2025), https://perma.cc/6FGM-27XS.

Richard Susskind, “Artificial Intelligence Could Replace Traditional Lawyers by 2035,” Times (London) (March 2025).

See David Freeman Engstrom, Lucy Ricca, & Natalie Knowlton, “Regulatory Innovation at the Crossroads: Five Years of Data on Entity-Regulation Reform in Arizona and Utah,” Stanford Law School (June 2, 2025), https://perma.cc/QL5D-8EW6.

Press Release, LexisNexis, “LexisNexis CounselLink Releases 2025 Trends Report Showing Large Law Command of Partner Rates” (April 22, 2025), https://perma.cc/XM8C-VTZJ.

E.g., “How to Harness AI for Justice,” 108 Judicature 42 (2024); OECD, “Governing With Artificial Intelligence: The State of Play and Way Forward in Core Government Functions” (Sept. 18, 2025), https://doi.org/10.1787/795de142-en; Shana Lynch, “Harnessing AI to Improve Access to Justice in Civil Courts,” Stanford HAI (March 4, 2025), https://perma.cc/6PGP-UG2J; Robert J. Couture, “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Law Firms’ Business Models,” Harvard Law School Center on the Legal Profession (Feb. 24, 2025), https://perma.cc/HYP6-SJQB.

Our understanding of bottlenecks is informed by systems analysis and theories of constraints in management science.

See Ed Walters, “Re-Regulating UPL in an Age of AI,” 8 Georgetown Law Technology Review 316 (2024).

Brian Oten, “Artificial Intelligence, Real Practice,” 28 North Carolina State Bar Journal 3 (fall 2023).

This report focuses on the U.S. legal system, but for more on how U.S. adversarialism differs from other legal systems, Leo You Li has compared the U.S. system with China and the U.K. and discussed what they might learn from each other. See, generally, Leo You Li, “Digitization, Adversarial Legalism, and Access to Justice Reforms,” 76 South Carolina Law Review 883 (2025).

Robert A. Kagan, Adversarial Legalism: The American Way of Law (2d ed., 2018).

Gillian K. Hadfield, “The Price of Law: How the Market for Lawyers Distorts the Justice System,” 98 Michigan Law Review 953 (2000), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.191908.

David Freeman Engstrom & Jonah B. Gelbach, “Legal Tech, Civil Procedure, and the Future of Adversarialism,” 169 University of Pennsylvania Law Review 1001 (2021).

David Freeman Engstrom & Nora Freeman Engstrom, “Legal Tech and the Litigation Playing Field,” in Legal Tech and the Future of Civil Justice 133 (David F. Engstrom, ed., 2023), https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009255301.

Hadfield, “The Price of Law,” supra note 17.

Li, supra note 15, at 892–93.

Arvind Narayanan & Sayash Kapoor, “AI as Normal Technology,” AI as Normal Technology (April 15, 2025), https://perma.cc/AQ2G-CQP3.

Justin Curl, “AI Is Just Starting to Change the Legal Profession,” Understanding AI (Jan. 15, 2026), https://perma.cc/N3BQ-5MKV.

Gillian Hadfield has written about the high costs of legal services for decades, and this section draws heavily on her work. E.g., Hadfield, “The Price of Law,” supra note 17; Gillian K. Hadfield, “The Cost of Law: Promoting Access to Justice Through the (Un)Corporate Practice of Law,” 38 International Review of Law and Economics 43 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2013.09.003; Gillian K. Hadfield & Deborah L. Rhode, “How to Regulate Legal Services to Promote Access, Innovation, and the Quality of Lawyering,” 67 Hastings Law Journal 1191 (2016); Gillian K. Hadfield, “More Markets, More Justice,” 148 Dædalus 37 (winter 2019), https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_00533; Gillian K. Hadfield, “Legal Markets,” 60 Journal of Economic Literature 1264 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20201330.

Hadfield, “The Price of Law,” supra note 17, at 969.

Id. at 972–73.

Id.

Engstrom & Gelbach, supra note 18, at 1062.

Hadfield, “The Price of Law,” supra note 17, at 973.

John Armour & Mari Sako, “Lawtech: Leveling the Playing Field in Legal Services?” in Legal Tech and the Future of Civil Justice 44, 44 (David F. Engstrom, ed., 2023), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3831481.

LexisNexis CounselLink, “2025 Trends Report” (2025), https://perma.cc/Q6K3-9SCW.

Id.

Hadfield, “Legal Markets,” supra note 24, at 1288.

Id.

Engstrom, Ricca, & Knowlton, supra note 9, at 5.

Id.

Hadfield, “More Markets, More Justice,” supra note 24.

Armour & Sako, supra note 30, at 44.

Hadfield, “More Markets, More Justice,” supra note 24, citing Clio, “2017 Legal Trends Report,” https://perma.cc/YS73-47QL.

Id.

Pew Charitable Trusts, “How Debt Collectors Are Transforming the Business of State Courts,” at 8 (May 6, 2020), https://perma.cc/999L-LQKA.

Michigan Justice for All Commission, Debt Collection Work Group, “Advancing Justice for All in Debt Collection Lawsuits: Report & Recommendations,” https://perma.cc/2SQT-M9SB (last visited Jan. 26, 2026).

Pew Charitable Trusts, supra note 41, at 2.

Id.

Institute for Justice, “Right to Provide Legal Advice,” https://perma.cc/Q2FN-8WEE (last visited Jan. 26, 2026).

Upsolve, Inc. v. James, 604 F.Supp.3d 97 (S.D.N.Y. May 24, 2022).

Upsolve, Inc. v. James, 155 F.4th 133 (2d Cir. Sept. 9, 2025).

Brian Oten, “Artificial Intelligence, Real Practice,” 28 North Carolina State Bar Journal 3 (fall 2023); see also Maria E. Berkenkotter & Linos Lipinsky de Orlov, “Can Robot Lawyers Close the Access to Justice Gap?” Colorado Lawyer (December 2024), at 40, https://perma.cc/YY73-XJDE.

New York State Bar Association Task Force on Artificial Intelligence, “Report and Recommendations to NYSBA House of Delegates” (April 6, 2024), https://perma.cc/6CXP-NLCA.

Sean Steward, “Are AI Lawyers a Legal Product or Legal Service?: Why Current UPL Laws Are Not Up to the Task of Regulating Autonomous AI Actors,” 53 Hofstra Law Review 391 (2025).

Walters, supra note 13, at 332.

Laurel A. Rigertas, “The Legal Profession’s Monopoly: Failing to Protect Consumers,” 82 Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics 1085 (2019).

Id.

Janson v. LegalZoom.com, Inc., 802 F. Supp. 2d 1053 (W.D. Mo. 2011).

LegalZoom.com, Inc. v. N.C. State Bar, No. 11 CVS 15111, 2015 NCBC 96 (N.C. Super. Ct. Oct. 22, 2015), https://perma.cc/U3LS-3C83.

Jason Tashea, “Nonlawyers at LegalZoom Performed Legal Work on Trademark Applications, UPL Suit Alleges,” ABA Journal (Dec. 20, 2017).

Class Action Complaint, Erasmus v. LegalZoom.com, Inc., No. ESX-L (N.J. Super. Ct. Law Div. Essex Cnty.), https://perma.cc/CR2L-ZV89.

Engstrom & Engstrom, supra note 19.

J. Maria Glover, “The Federal Rules of Civil Settlement,” 87 New York University Law Review 1713 (2012).

Kagan, supra note 16.

Engstrom & Gelbach, supra note 18, at 1043.

John S. Beckerman, “Confronting Civil Discovery’s Fatal Flaws,” 84 Minnesota Law Review 505 (2000), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.199068.

Frank H. Easterbrook, “Discovery as Abuse,” 69 Boston University Law Review 635 (1989).

Charles M. Yablon, “Stupid Lawyer Tricks: An Essay on Discovery Abuse,” 96 Columbia Law Review 1618 (1996).

Engstrom & Gelbach, supra note 18.

Alexandra Lahav emphasized the shortage of reliable evidence in an article calling for courts to log discovery requests, so researchers can better assess the extent of discovery abuse and costs. While she would argue discovery is not as big of a problem as lawyers claim, her main point is that there is insufficient evidence to be confident either way. And even she agrees that where discovery is actively employed, it is very expensive, even if she thinks these costs are justified by the higher dollar amounts at stake. See Alexandra D. Lahav, “A Proposal to End Discovery Abuse,” 71 Vanderbilt Law Review 2037 (2019).

Engstrom & Engstrom, supra note 19, at 138.

Hadfield, “Legal Markets,” supra note 24.

Id.

Engstrom & Gelbach, supra note 18, at 1052–53.

Hadfield, “The Price of Law,” supra note 17.

Id.

Id.

Id.

John C. Coates IV, “Why Have M&A Contracts Grown? Evidence From Twenty Years of Deals” (Harvard Law School, Working Paper, Oct. 26, 2016), https://perma.cc/JQ8X-R6KV.

Isabel Wagner, “Privacy Policies Across the Ages: Content of Privacy Policies 1996–2021,” 26 ACM Transactions on Privacy and Security, Article 32, at 1 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1145/3590152.

Coates IV, supra note 75.

Claire A. Hill & Christopher King, “How Do German Contracts Do as Much With Fewer Words?“ 79 Chicago-Kent Law Review 889 (2004).

See, e.g., Ronald J. Gilson, “Value Creation by Business Lawyers: Legal Skills and Asset Pricing,” 94 Yale Law Journal 239 (1984); Steven L. Schwarcz, “Explaining the Value of Transactional Lawyering,” 12 Stanford Journal of Law, Business & Finance 486 (2007).

Yonathan A. Arbel, “Judicial Economy in the Age of AI,” 96 Colorado Law Review 549 (2025), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4873649.

Id.

Li, supra note 15.

Human Rights Watch, “Rubber Stamp Justice” (January 2016), https://perma.cc/JV3T-72ZM.

Arbel, supra note 80.

Pedro Nakamura, “AI Is Helping Judges to Quickly Close Cases, and Lawyers to Quickly Open Them,” Rest of World (Sept. 25, 2025), https://perma.cc/GF8G-SH3J.

See, e.g., Victor Tangermann, “Estonia Is Building a ‘Robot Judge’ to Help Clear Legal Backlog,” Futurism (March 25, 2019), https://perma.cc/GC2W-BLT5.

Jerry M. Gewirtz, “Artificial Intelligence May Assist, but Can Never Replace, the Judicial Decision-Making Process of Human Judges,” 98 Florida Bar Journal 6, 8 (November/December 2024), https://perma.cc/WT33-LYBL.

Justin Curl, Peter Henderson, Kart Kandula, & Faiz Surani, “Judges Shouldn’t Rely on AI for the Ordinary Meaning of Text,” Lawfare (May 22, 2025).

Marcin Górski, “Why a Human Court?,” 18 EUCrim 83 (2023), https://perma.cc/P6W6-RXX9.

Unikowsky, “Should AI Replace Law Clerks?,” supra note 7.

Brooke Auxier, Lee Rainie, Monica Anderson, Andrew Perrin, Madhu Kumar, & Erica Turner, “Americans and Privacy: Concerned, Confused and Feeling Lack of Control Over Their Personal Information,” Pew Research Center (Nov. 15, 2019), https://perma.cc/Z5XZ-QVBT.

See, e.g., Hon. C. S. Maravilla, “A(I)ccess to Justice: How AI and Ethics Opinions Approving Limited Scope Representation Support Legal Market Consolidation,” 40 Georgia State University Law Review 957 (2024); Bruce A. Green & M. Ellen Murphy, “Replacing This Old House: Certifying and Regulating New Legal Services Providers,” 76 Washington University Journal of Law and Policy 45 (2025); Joseph J. Avery, Patricia Sánchez Abril, & Alissa del Riego, “ChatGPT, Esq.: Recasting Unauthorized Practice of Law in the Era of Generative AI,” 26 Yale Journal of Law & Technology 64 (2023), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5152523; Mia Bonardi & L. Karl Branting, “Certifying Legal AI Assistants for Unrepresented Litigants: A Global Survey of Access to Civil Justice, Unauthorized Practice of Law, and AI,” 26 Columbia Science & Technology Law Review 1 (2025), https://doi.org/10.52214/stlr.v26i1.13336.

State supreme courts regulate the practice of law in the U.S., though some courts have delegated this task to bar associations and receive input from state legislators. The exact process by which these regulations change varies by jurisdiction, so we refer to the recommended actor as state courts for simplicity. For more on how professional regulations are enacted and modified, see Lucy Ricca & Thomas Clarke, “The Bar Re-imagined: Options for State Courts to Re-structure the Regulation of the Practice of Law,” Stanford Law School Deborah L. Rhode Center on the Legal Profession (September 2023), https://perma.cc/WP7L-GWMY.

Engstrom, Ricca, & Knowlton, supra note 9, at 11.

David Autor, “Applying AI to Rebuild Middle Class Jobs” (National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 32140, February 2024), https://perma.cc/VBA4-JSFL.

Id.

Green & Murphy, supra note 93.

Avery, Abril, & del Riego, supra note 93.

Id.

Steward, supra note 50.

Drew Simshaw, “Toward National Regulation of Legal Technology: A Path Forward for Access to Justice,” 92 Fordham Law Review 1 (2023).

See, generally, R. Matthew Black, “Extra Law Prices: Why MRPC 5.4 Continues to Needlessly Burden Access to Civil Justice for Low- to Moderate-Income Clients,” 25 Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice 499 (2019); Robert Saavedra Teuton, “One Small Step and a Giant Leap: Comparing Washington, D.C.’s Rule 5.4 With Arizona’s Rule 5.4 Abolition,” 65 Arizona Law Review 223 (2023); Stephen P. Younger, “The Pitfalls and False Promises of Nonlawyer Ownership of Law Firms,” 132 Yale Law Journal Forum 80 (2022); Gillian K. Hadfield, “Higher Demand, Lower Supply? A Comparative Assessment of the Legal Resource Landscape for Ordinary Americans,” 37 Fordham Urban Law Journal 129 (2010); Gillian K. Hadfield & Deborah L. Rhode, “How to Regulate Legal Services to Promote Access, Innovation, and the Quality of Lawyering,” 67 Hastings Law Journal 1191 (2016); Jonathan T. Molot, “What’s Wrong With Law Firms? A Corporate Finance Solution to Law Firm Short-Termism,” 88 Southern California Law Review 1 (2014).

Engstrom, Ricca, & Knowlton, supra note 9.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Hadfield, “More Markets, More Justice,” supra note 24.

Id.

See Daniel Schwarcz, Sam Manning, Patrick Barry, David R. Cleveland, J.J. Prescott, & Beverly Rich, “AI-Powered Lawyering: AI Reasoning Models, Retrieval Augmented Generation, and the Future of Legal Practice,” Journal of Law & Empirical Analysis (forthcoming 2026), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5162111; Lauren Martin, Nick Whitehouse, Stephanie Yiu, Lizzie Catterson, & Rivindu Perera, “Better Call GPT, Comparing Large Language Models Against Lawyers” (Jan. 24, 2024) (unpublished manuscript), https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2401.16212; Jonathan H. Choi, Amy Monahan, & Daniel Schwarcz, “Lawyering in the Age of Artificial Intelligence,” 109 Minnesota Law Review 147 (2024), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4626276.

Sayash Kapoor, Peter Henderson, & Arvind Narayanan, “Promises and Pitfalls of Artificial Intelligence for Legal Applications,” Journal of Cross-disciplinary Research in Computational Law (2024), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4695412.

Chuck Dinerstein, “When AI Takes Over: The Hidden Cost of Technological Progress,” American Council on Science and Health (April 1, 2025), https://perma.cc/9C6X-JAZT.

Id.

“History of the Reforms,” https://perma.cc/XF4F-ZVSV (last visited Jan. 26, 2026).

“Major Legal Regulators Fall Short in Latest Performance Assessment,” https://perma.cc/4YUS-7RD5 (last visited Jan. 26, 2026).

Hadfield, “More Markets, More Justice,” supra note 24.

Sam Tobin, “British Legal Regulator Criticised Over Collapse of Law Firm Axiom Ince,” Reuters (Oct. 29, 2024).

See John Hyde, “Legal Services Board Slams SRA Failings in Damning Report,” Law Gazette (March 31, 2025), https://perma.cc/3N9W-6K2G; Oscar Glyn, “SRA Faces Closer Supervision After ‘Failing to Protect Public’,” Law.com (Oct. 17, 2025).

Daniel Schwarcz, “Regulating Insurance Sales or Selling Insurance Regulation?: Against Regulatory Competition in Insurance,” 94 Minnesota Law Review 1707 (2010).

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, “Adversarial vs. Inquisitorial Legal Systems,” E4J University Module Series, https://perma.cc/Z7XA-D46A (last visited Jan. 26, 2026).

Federal Rule of Evidence 706.

Bradford H. Charles, “Rule 706: An Underutilized Tool to Be Used When Partisan Experts Become ‘Hired Guns’,” 60 Villanova Law Review 941 (2016).

Id.

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 53.

Shira A. Scheindlin & Jonathan M. Redgrave, “Special Masters and E-Discovery: The Intersection of Two Recent Revisions to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,” 30 Cardozo Law Review 347 (2008).

Id.

Soia Mentschikoff, “Commercial Arbitration,” 61 Columbia Law Review 846 (1961), https://doi.org/10.2307/1120097.

Christopher R. Drahozal, ”Arbitration Costs and Forum Accessibility: Empirical Evidence,” 41 University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform 813 (2008), https://doi.org/10.36646/mjlr.41.4.arbitration.

Theodore Eisenberg, Geoffrey P. Miller, & Emily Sherwin, “Arbitration’s Summer Soldiers: An Empirical Study of Arbitration Clauses in Consumer and Nonconsumer Contracts,” 41 University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform 871 (2008), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1076968.

Amberlee B. Conley, “You Can Have Your Day in Court—But Not Before Your Day in Mandatory, Nonbinding Arbitration: Balancing Practicalities of State Arbitration,” 104 Iowa Law Review 325 (2018).

Christopher R. Drahozal & Quentin R. Wittrock, “Is There a Flight From Arbitration?,” 37 Hofstra Law Review 71 (2008).

Michael J. Broyde & Yiyang Mei, “Don’t Kill the Baby! The Case for AI in Arbitration,” 21 New York University Journal of Law & Business 1 (2024).

Id.

David Horton, “Forced Robot Arbitration,” 109 Cornell Law Review 679 (2024).

Robert Walters, “Robots Replacing Human Arbitrators: The Legal Dilemma,” 34 Information & Communications Technology Law 129 (2025), https://doi.org/10.1080/13600834.2024.2408155.

David S. Schwartz, “Mandatory Arbitration and Fairness,” 84 Notre Dame Law Review 1247 (2009); Jessica Silver-Greenberg & Robert Gebeloff, “Arbitration Everywhere, Stacking the Deck of Justice,” New York Times (Oct. 31, 2015).

Stephen J. Ware, “The Centrist Case for Enforcing Adhesive Arbitration Agreements,” 23 Harvard Negotiation Law Review 29 (2017).

Peter B. Rutledge & Christopher R. Drahozal, “Contract and Choice,” 2013 Brigham Young University Law Review 1 (2013).

Amanda R. Witwer, Lynn Langton, Duren Banks, Dulani Woods, Michael J.D. Vermeer, & Brian A. Jackson, “Online Dispute Resolution: Perspectives to Support Successful Implementation and Outcomes in Court Proceedings,” RAND Corporation (2021), https://perma.cc/TD7Q-HGM7.

See Broyde & Mei, supra note 131, at 168–172.

See Richard Re & Alicia Solow-Niederman, “Developing Artificially Intelligent Justice,” 22 Stanford Technology Law Review 242, 278–80 (2019).

Maria L. Marcus, “Judicial Overload: The Reasons and the Remedies,” 28 Buffalo Law Review 111, 132–33 (1979).

Bert I. Huang, “Lightened Scrutiny,” 124 Harvard Law Review 1109 (2011).

Peter S. Menell & Ryan Vacca, “Revisiting and Confronting the Federal Judiciary Capacity ‘Crisis’: Charting a Path for Federal Judiciary Reform,” 108 California Law Review 789 (2020) (quoting “National Court of Appeals Act, Hearings on S. 2762 and S. 3423 Before the Subcommittee on Improvements in Judicial Machinery of the Committee on the Judiciary,” 94th Cong. i, 26–37 (1976)).

Menell & Vacca, supra note 143.

Arbel, supra note 80.

Id.

Shaoli Katana, “MSBA’s 2024 Legislative Wins,” Minnesota State Bar Association, https://perma.cc/AP6Q-FQ8V (last visited Jan. 26, 2026).

S. 1821, 119th Cong. (2025).

Deborah L. Rhode, “Access to Justice: Connecting Principles to Practice,” 17 Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics 369 (2004).

Christian Veith, Michael Bandlow, Michael Harnisch, Hariolf Wenzler, Markus Hartung, & Dirk Hartung, “How Legal Tech Will Change the Business of Law,” Boston Consulting Group (2016), https://perma.cc/2EM6-B4YB.

Andy Teichholz, “The Modern General Counsel: Legal Advisor and Strategic Business Partner,” Corporate Counsel Business Journal (2024), https://perma.cc/26ZK-KDBS.

Thomson Reuters, “Future of Professionals Report 2024” (2024), https://perma.cc/HHA4-7DUV.

Marjorie Richter, “How AI Is Transforming the Legal Profession,” Thomson Reuters Blog, https://perma.cc/Z9ZL-BGXA (last visited Jan. 26, 2026).

Veith et al., supra note 150.

Richter, supra note 153.

Thomson Reuters, supra note 152.

Teichholz, supra note 151.

DRI Center for Law and Public Policy Artificial Intelligence Working Group, “Artificial Intelligence in Legal Practice: Benefits, Considerations, and Best Practices” (2024), https://perma.cc/8X6E-BC25.

Cynthia Hardy & Steve Maguire, “Institutional Entrepreneurship and Change in Fields,” in Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism (Royston Greenwood, Christine Oliver, Thomas B. Lawrence, Renate E. Meyer, Cynthia Hardy, & Steve Maguire, eds., 2d ed., 2017), https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446280669.n11.