America, it’s time to refamiliarize yourself with Ring.

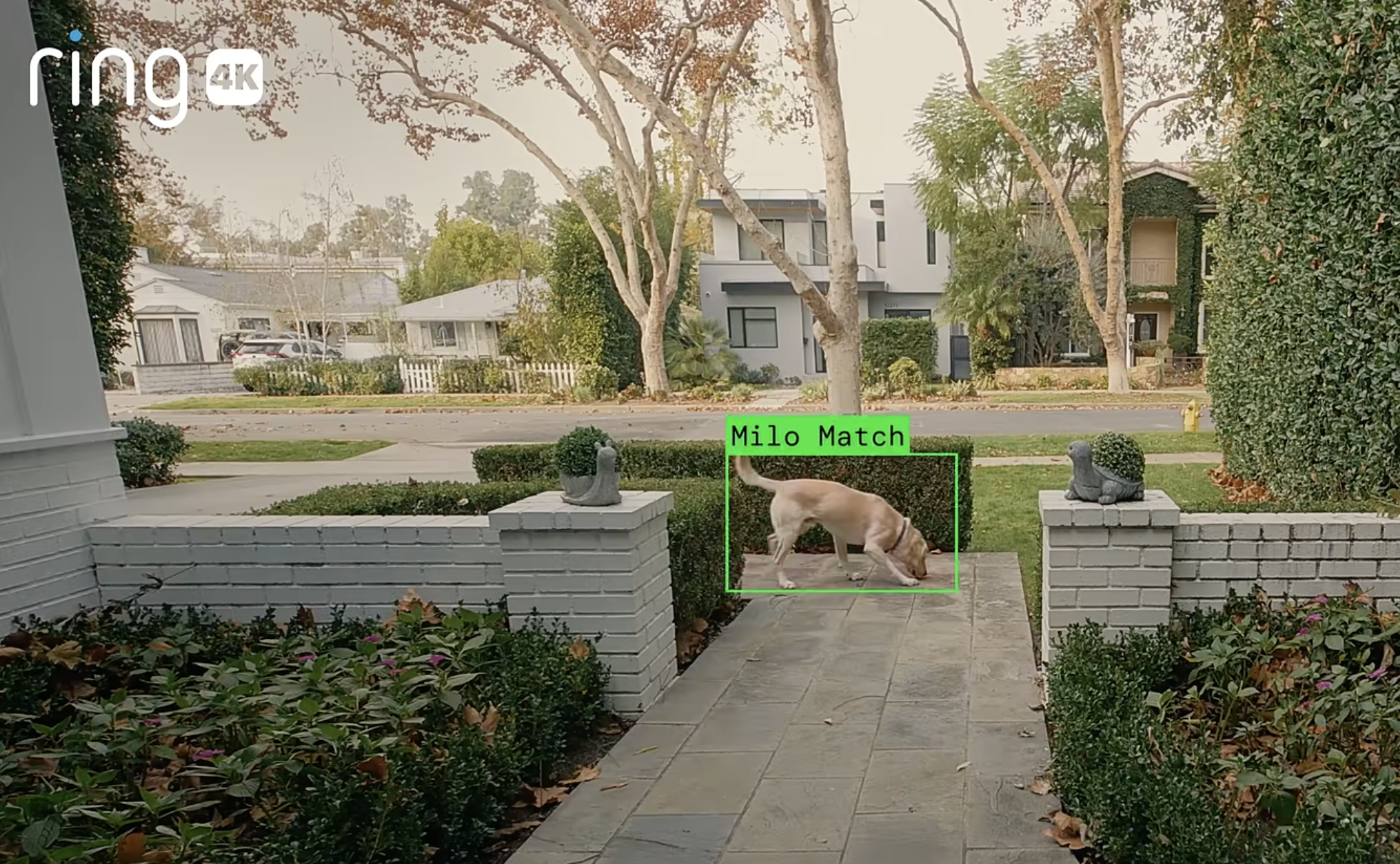

At Sunday’s Super Bowl, Ring advertised “Search Party,” a cute, horrifyingly dystopian feature nominally designed to turn all of the Ring cameras in a neighborhood into a dragnet that uses AI to look for a lost dog: “One post of a dog’s photo in the Ring app starts outdoor cameras looking for a match,” Ring founder Jamie Siminoff said in the Super Bowl commercial. “Search Party from Ring uses AI to help families find lost dogs.” Onscreen, an AI-powered box forms around a missing dog: “Milo Match,” it says. “Since launch, more than a dog a day has been reunited with their family. Be a hero in your neighborhood with Search Party. Available to everyone for free right now.”

It does not take an imagination of any sort to envision this being tweaked to work against suspected criminals, undocumented immigrants, or others deemed ‘suspicious’ by people in the neighborhood. Many of these use cases are how Ring has been used by people on its dystopian “Neighbors” app for years. Ring rose to prominence as a piece of package theft prevention tech owned by Amazon and by forming partnerships with local police around the country, asking them to shill their doorbell cameras to people in their neighborhoods in return for a system that allowed police to request footage from individual users without a warrant.

Chris Gilliard, a privacy expert and author of the upcoming book Luxury Surveillance, told 404 Media these features and its Super Bowl ad are “a clumsy attempt by Ring to put a cuddly face on a rather dystopian reality: widespread networked surveillance by a company that has cozy relationships with law enforcement and other equally invasive surveillance companies.”

Unlike, say, data analytics giant Palantir or some other high-profile surveillance companies, Ring is a surveillance network that homeowners have by and large deployed themselves, powered by fear mongering against our neighbors and unfettered consumerism.

After a lot of criticism in the late 2010s over its police contracts and its terrible security settings that resulted in hackers breaking into a series of indoor Ring cameras to terrorize children and families, Ring somehow found a way to more or less fly under the radar the last few years as a critical part of our ever-expanding surveillance state. It did this by scaling back police partnerships that were so critical to its growth but that received lots of scrutiny from journalists and privacy advocates. Siminoff left Ring in 2023, but returned last year; in his absence, Ring explicitly sought to take on a softer tone by branding itself as more or less as a device that could be used to film viral moments on people’s porches. It turned its owners into mini cops who would complain about delivery people who didn’t drop a package in the correct spot; who became hyperaware of the comings and goings of their friends, spouses, and children, or who might catch a potentially sharable moment when someone slipped on an icy porch or whatever. Part of this strategy included creating a short-lived reality TV show called Ring Nation, which consisted of precious little moments filmed through Ring cameras.

When Siminoff returned last year, he immediately sought to re-establish many of Ring’s partnerships with police, and set an explicit goal of injecting more AI into Ring cameras and trying to “revolutionize how we do our neighborhood safety.”

“Ring is rolling back many of the reforms it’s made in the last few years by easing police access to footage from millions of homes in the United States. This is a grave threat to civil liberties in the United States,” Matthew Guariglia of the Electronic Frontier Foundation wrote shortly after Siminoff’s return. “This is most likely about Ring cashing in on the rising tide of techno-authoritarianism, that is, authoritarianism aided by surveillance tech. Too many tech companies want to profit from our shrinking liberties.”

Even in Siminoff’s absence, Ring had always, explicitly been intended to assist law enforcement. In a series of investigations we did back at VICE (mostly written by Caroline Haskins, who is still covering surveillance at WIRED), we uncovered thousands of pages of documents, emails, and chats via public records requests and leaks that highlighted Ring’s surveillance ambitions. The company threw parties for police, employees wore “FUCK CRIME” shirts to internal parties, and helped police facilitate the retrieval of footage from its customers’ cameras if they initially refused to cooperate. It helped police set up elaborate, completely useless package “sting” operations designed to catch criminals but that did not result in any arrests. Ring gave cops devices that they could raffle off to people in their towns, gave police “heat maps” of where its customers lived, used its social media accounts to post footage of supposed suspicious people, and incentivized customers to create “Digital Neighborhood Watch” groups that could earn them swag if they used their Ring cameras to report suspicious activity to police.

With Ring’s recent partnership with Flock, which will further facilitate the sharing of video footage with police, and its new Search Party feature, the message is clear: Ring is still, again, and always will be in the business of leveraging its network of luxury surveillance consumers as a law enforcement tool. After years of saying it wasn’t doing facial recognition and that it was focused more on “object recognition,” it has now explicitly launched “friendly” versions of facial recognition and facial recognition-adjacent technologies: “Search Party” is essentially specific dog recognition (for now), and a beta product called “Familiar Faces” specifically identifies people you know when they’re at your door. “Alexa Guard identifies who’s who,” the product’s website reads. “With Familiar Faces, easily tag your family and friends in the Ring app so your 2k and 4k cameras can notify you when someone is spotted.”

Ring has always been a surveillance tool, but adding AI analysis and networking the devices together—like is being promised with Search Party—turns discrete pieces of tech into massive, automated surveillance dragnets.

“Siminoff’s return was a hard pivot back to, in his words, the ‘crime fighting’ element and away from the softer tone they had tried to establish with Ring as a fun way to interact with people in your community,” Gilliard said. “But I think it’s becoming very obvious to people how these systems are being deployed against their neighbors in oppressive ways, and they are beginning to reject them, particularly since there is no strong evidence that they prevent crime or make people safer.”

The YouTube comments on Ring’s Super Bowl ad are almost uniformly negative, with people noting “this is like the commercial they show at the beginning of a dystopian sci fi film to quickly show people how bad things have gotten,” “are we really supposed to believe that the main intent for this is lost pets,” and “glad people are freaking out. This is dystopia becoming reality.”

Ring’s poorly defined partnership with Flock in particular has been the subject of various viral posts and public backlash. Many people have suggested that this partnership is evidence that Ring camera footage will be shared with ICE. At the moment there’s not enough evidence to explicitly say that that’s the case.

The supposed vector goes something like this: Ring says it will partner with Flock, which is used by thousands of local police departments. As we have reported, some of those police departments have performed Flock license plate lookups for ICE. It’s too early to say whether Ring footage will eventually end up with ICE, but the fact that people immediately drew that conclusion and understood the possible method of information sharing shows that surveillance companies can no longer hide behind viral videos of delivery drivers dancing. It’s a mask off moment, and people know it: “In Amazon’s alliance with this administration, it’s become more clear than ever that Ring is an extension of the carceral state,” Gilliard said. “An emotionally charged Super Bowl ad won’t change that.”