The IRS open sourced much of its incredibly popular Direct File software as the future of the free tax filing program is at risk of being killed by Intuit’s lobbyists and Donald Trump’s megabill. Meanwhile, several top developers who worked on the software have left the government and joined a project to explore the “future of tax filing” in the private sector.

Direct File is a piece of software created by developers at the US Digital Service and 18F, the former of which became DOGE and is now unrecognizable, and the latter of which was killed by DOGE. Direct File has been called a “free, easy, and trustworthy” piece of software that made tax filing “more efficient.” About 300,000 people used it last year as part of a limited pilot program, and those who did gave it incredibly positive reviews, according to reporting by Federal News Network.

But because it is free and because it is an example of government working, Direct File and the IRS’s Free File program more broadly have been the subject of years of lobbying efforts by financial technology giants like Intuit, which makes TurboTax. DOGE sought to kill Direct File, and currently, there is language in Trump’s massive budget reconciliation bill that would kill Direct File. Experts say that “ending [the] Direct File program is a gift to the tax-prep industry that will cost taxpayers time and money.”

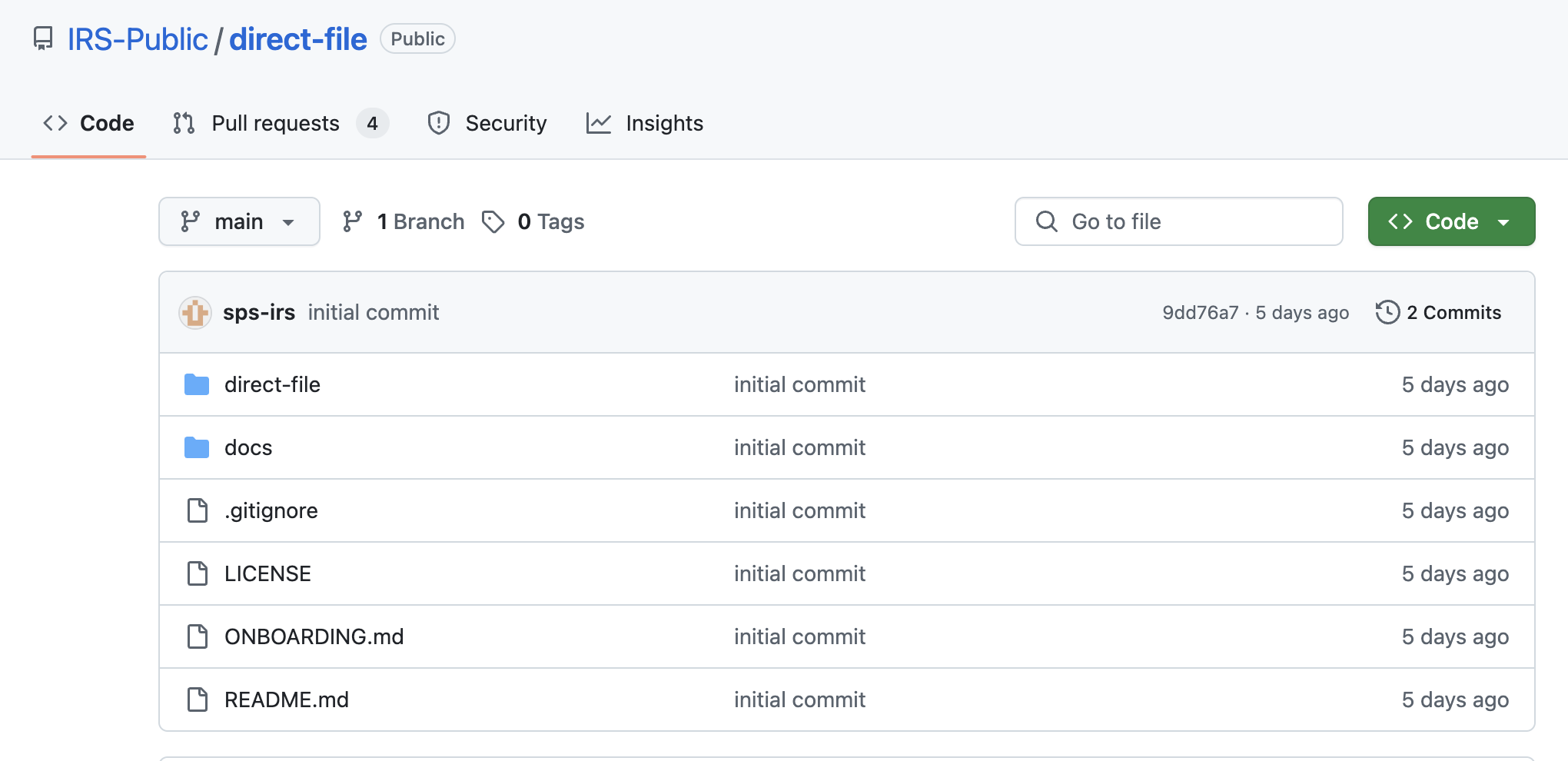

That means it’s quite big news that the IRS released most of the code that runs Direct File on Github last week. And, separately, three people who worked on it—Chris Given, Jen Thomas, Merici Vinton—have left government to join the Economic Security Project’s Future of Tax Filing Fellowship, where they will research ways to make filing taxes easier, cheaper, and more straightforward. They will be joined by Gabriel Zucker, who worked on Direct File as part of Code for America.

“Establishing trust with taxpayers was core to our approach for designing and building Direct File,” Given wrote on his personal blog. “By creating the most accurate option for filing, by making taxes accessible to all, by keeping taxpayer data secure, and now, by publicly sharing Direct File’s code, the Direct File team showed our dedication to earning taxpayers’ trust.”

When the code for Direct File was released on Github last week, some people speculated that, because of the political pressure against it, its release must have been an act of resistance by someone within the IRS. But the open sourcing of the program was always part of the plan, and was required by a law called the SHARE IT Act. It happened “fully above board, which is honestly more of a feat!,” Given told 404 Media. “This has been in the works since last year.”

Initial analyses of the code suggest that it is very good and will be useful to people developing software in this field.

In a report published last year, the IRS suggested that open sourcing Direct File would have numerous benefits: “First, it would enable public scrutiny of that code and invite independent groups to assess its accuracy and report potential issues. Second, other tax administrators, both in states and internationally, could build upon and contribute to the IRS’s work, improving the robustness of the software over time and providing additional public value,” it wrote. “Finally, the IRS’s work could serve as a reference for implementation of the Internal Revenue Code as computer code, enabling businesses and others to incorporate the IRS’s code into their own software and increasing the vibrancy of the tax ecosystem.”

Given told 404 Media that Direct File relies in part on internal IRS systems (like the ability to pull W-2 data directly from the IRS, and internal IRS authentication systems), so it cannot be run off-the-shelf using only the code that was released. “Being from the IRS, Direct File doesn’t file state tax returns, and relies on integrations with tools provided by state revenue agencies to facilitate that task, and unnecessary complication if you’re rolling your own filing tool and you aren’t the IRS,” he said.

Vinton said that the Direct File team worked for a long time knowing that there were people within government and external companies who did not want the IRS to create Direct File. “We had to really focus and not get distracted by all of the noise, wherever the noise was coming from. The way you get through it is you keep your head down and not get distracted by focusing on our users. That is how we found our way through this,” she said. “We always assumed there would be people gunning for it, but we also knew it was something people wanted. We knew it was an idea whose time had come. The noise now is, well, it’s a situation that has been brewing for a while.”

Even though Direct File is not runnable off the shelf, the codebase itself is still incredibly valuable and can help developers guide the next generation of tax filing software.

“I think there’s also a lot of value,” Given said. “Each of the more than 700 screens of Direct File was vetted by the IRS Office of Chief Counsel. It asks questions no other tool asks, and provides an authoritative, plain language interpretation of a significant swath of the Internal Revenue Code.”

Vinton told 404 Media in a phone call that the open sourcing of Direct File “is just good government.”

“All code paid for by taxpayer dollars should be open source, available for comment, for feedback, for people to build on and for people in other agencies to replicate. It saves everyone money and it is our [taxpayers’] IP,” she said. “This is just good government and should absolutely be the standard that government technologists are held to.”

Given said that at the Economic Security Project, he and his colleagues will first start by documenting how Direct File was made and what it does, and they will hopefully work with outside groups to come up with new ways to make tax filing easier.

They will “suggest some opportunities to continue to advance access to filing and tax benefits, both short-term things that can be done by states and/or nonprofits and longer-term policy ideas,” he said. “I know there’s a lot of interest in how to keep Direct File’s lights on, even without the IRS, but I think the loss of that key player necessitates a more imaginative approach than just keeping on keeping on.”

The group is also considering using its experience creating Direct File—which involved parsing the incredibly complex tax code—to think up new ways to explain how the tax code works and to consider how that process could be applied to other complicated government programs.

“I’ve had conversations about the potential of the Direct File ‘Fact Graph’ as civic infrastructure. When you break it down, taxes are just the gnarliest and most complex form in all of government, and a solution that demonstrably scales to that challenge could also have many other uses (think applying for benefit programs),” he said. “I think there could be interest in continuing that work to make not only a future Direct File easier to build, but to enable more Direct File-like services in the future. But there’s the perennial question of whether it’s worth focusing on the technology when it’s generally the people/political problems that are the bigger blockers to delivering great government services.”

Vinton said that she hopes the learnings of Direct File can eventually be applied to other government processes, and that it’s an example of government working very well.

“We had highly empowered, autonomous teams doing this work,” she said. “I think that should be a model for how government agencies should work. That’s what I want to do is start thinking through different lessons, leadership lessons, executive level lessons for how government institutions can learn from Direct File. There’s a lack of trust in government that’s been around for a while. DirectFile increased trust in the IRS by 86 percent among people who used it. You go in, you complete your experience and transaction and people will not just come back but it will increase their trust. It helps our institutions and our democracy.”